The Changing Urban Political Order and Politics of Space

A Study of Hong Kong's POSPD Policy

Yang Yu (Renmin University of China)

There is an increasing tension between the land development regime and the grassroots anti-growth coalition in Hong Kong, where public spaces have played a critical role. After the transfer of sovereignty in 1997, Hong Kong's society seemed to decline from prosperous to turbulent, which has aroused public concern in recent years. Many attribute the current dilemma to the regime transition from the British Hong Kong Government to the Hong Kong Autonomous Government and thus conclude that the transitional process of regime change is driven by exogenous factors.

Hong Kong is widely well-known as the template of laissez-faire capitalism worldwide, which has the tradition of low direct taxation. However, my research questions such stereotypes by exploring the established land development regime consisting of the government and private developer tycoons facilitated by quasi-governmental organizations. In reality, far from being non-interventionist, this regime is characterized by liberal-democratic and corporatist-oligarchic elements, which carries out the policy of high land price via intentionally controlling the annual land sale to maintain the low direct taxation. Under the policy, other public policies have been channeled into being pro-growth by the regime. Through the lens of the policy of Public Open Spaces in Private Development (POSPD), this research illustrates the influence of the land development regime upon the public spaces it produces and the counteractive impact of POSPD on the established regime. Two representative spatial protests, the Hijacking Public Space Movement in Times Square and the Occupy Central Movement in the HSBC Headquarters, are explored to illustrate how awakening civil power challenges the regime and how the regime resists and defends its realm.

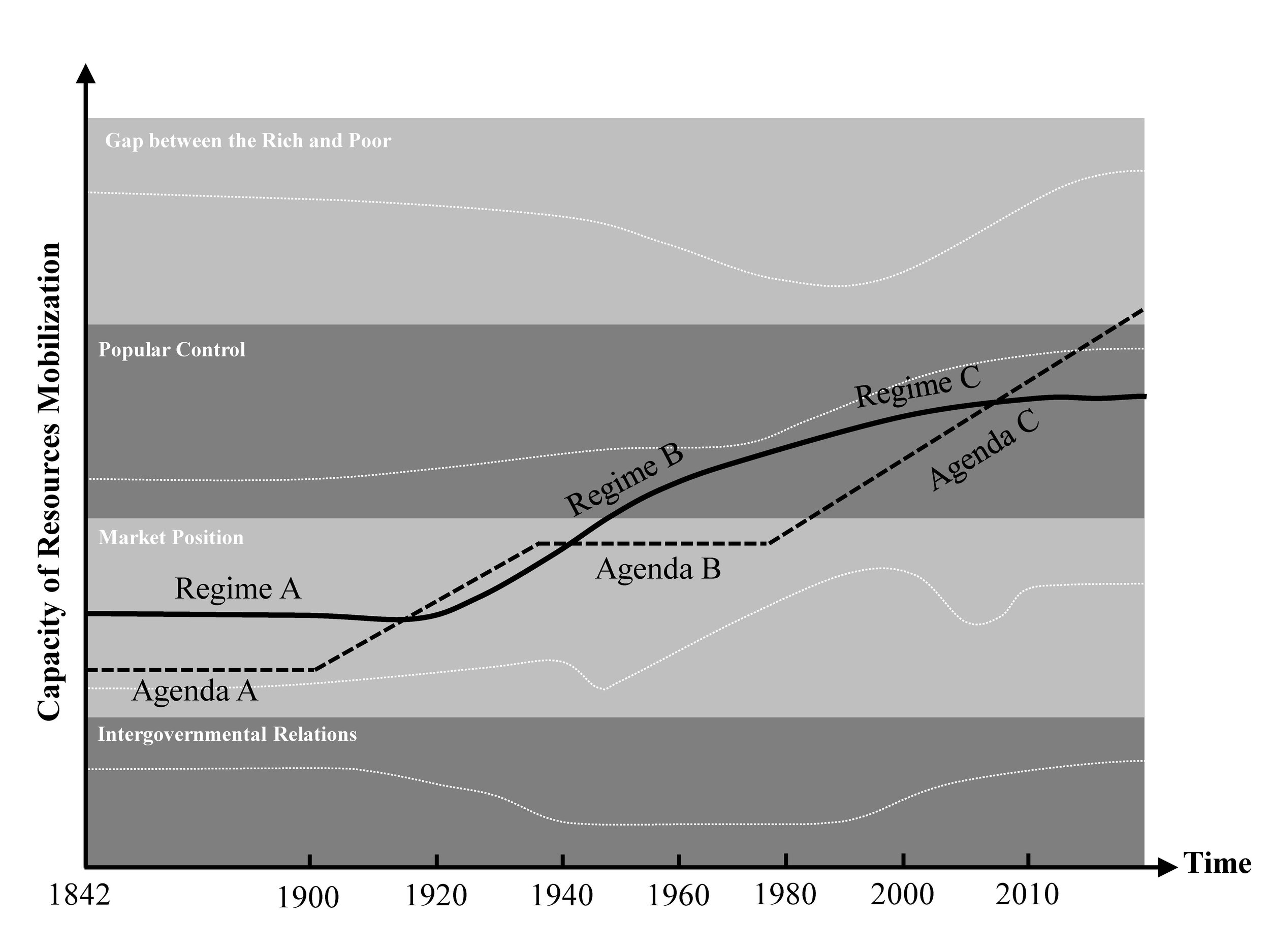

Many argue that the 1997 handover marks the punctuated regime change that explains Hong Kong's falling afterwards. But, by applying the theoretical framework of urban political order to the case of Hong Kong, this research finds that the regime transition is more gradual than punctuated as a multidimensional process. Each new regime is forged within the context of the old one. Before the 20th Century, the regime was dominated by the colonial government and local British elites (Regime A), with the main agenda (Agenda A) of stabilizing colonial rule and serving the interests of British businessmen. The power of local Chinese was fairly weak, so low regime resources were needed, and a policy of racial discrimination was adopted to successfully suppress potential resistance. From the 1900s to the 1940s, with the rising local Chinese society, racial discrimination policies became increasingly insufficient for political stability, and more resources were required. From the 1940s to the 1980s, to overcome the governing crisis, the main agenda gradually altered to the use of economic growth as the alternative to political development (Agenda B), and the regime increasingly absorbed Chinese business elites (Regime B). Starting from the 1980s, the withdrawals of British business elites resulted in the monopoly of Chinese business elites. Under the support of the Chinese government, who prioritized a smooth handover, this monopoly expanded to multi-industry after 1997. The regime became dominated by the Hong Kong Autonomous Government and local Chinese business elites (Regime C). To a large extent, the post-colonial regime inherited the colonial one and even the far-reaching handover failed to lead to a punctuated regime transition. Nevertheless, the radical political reform in the early 1990s accelerated popular control, significantly altering the policy agenda from economic growth to social welfares (Agenda C). This has gradually exceeded the current regime's capacity of resource mobilization, which led to political instability.

In conclusion, the land development regime in Hong Kong originates from the British colonial rule that lasted until now. Thus, the current governing dilemma rooted far before 1997 can be explained as the inapplicability of the social production model of power in the postindustrial era with an emerging civil society and more fragmented resources and there is an increasing need for a social corrective capacity that focuses on wealth redistribution. POSPD development in Hong Kong shows interplay with regime transition, or political sociospatial dialectic. The incentive policy started in the 1960s, when laissez-faire ideology was popular and the main agenda was promoting economic growth. In the 1970s, the involvement of privileged British real estate giants redirected the policy to facilitate the land development regime. In the transitional period from the 1980s and 1990s, rising Chinese real estate giants replaced their British counterparts in the regime, and promoted the construction upsurge of large-scale POSPDs through CDA policy. With the fundamental contextual changes since 1997, the urban political order has been in transition, and the significance of POSPD as political space for the anti-growth coalition has become evident.

Yang Yu is assistant professor in the Department of Urban Planning and Management at Renmin University of China. His research interests lie in regime and institutional analyses of urban development and urban planning laws in China.