From Progressive Cities to Resilient Cities

Lessons from History for New Debates in Equitable Adaptation to Climate Change

Linda Shi (Cornell University)

Advocates for a Green New Deal forcibly argue that climate action must be racially just and transform institutions that govern social welfare. However, these proposals have focused on cutting carbon emissions and been vague on how the country should adapt to an already changing climate. Early proposals suggest that a Green New Deal for adaptation should emphasize large-scale investments in infrastructure for marginalized communities. But evidence suggests that adaptation infrastructure projects can worsen the well-being of the most vulnerable. For instance, cities tend to prioritize investments for high value real estate or enforce land use and other regulations more stringently on those with less political voice. There also isn’t enough money to protect everyone and every place. Given the prevailing dynamics of urban development, an adaptation moon-shot must go far beyond giving the poor a sea wall or sand dune.

Over the past five years, some of the most prominent adaptation professionals and environmental justice organizations have published reports (see list at the end of the post) detailing what they think equitable and just climate adaptation should look like. My study, recently published in Urban Affairs Review, synthesizes what ten of these reports propose and then places these proposals in conversation with historic urban progressive movements. In short, these advocates forcefully argue for recognizing racial injustice in climate planning. They identify specific procedural changes that governments can take to achieve a fair playing ground for adaptation planning and decision-making and more fairly distribute investments in resiliency that benefit poor. However, these proposals, made before the 2018 elections, were quite muted on taxation, regulation, or legal, economic, or other structural reform. Many argued for building community political power, but more often by forging new alliances rather than gaining direct political power.

Lessons from history, especially from the radical progressivism of the 1970s, suggest that adaptation justice advocates today must not only address the needs and interests of marginalized communities, but also help envision and reform urban policies at multiple scales to achieve durable gains in community wellbeing. Historically, progressives often failed to achieve their goals because racial, class, and geographic divisions led to compromising compromises or to the isolation of these aspirations to a few places. Advocates of equitable adaptation today risk repeating these experiences or abdicating opportunities to reform the broader structures driving urban spatial inequality, exclusion, and displacement. The recent leftward shift in national politics may provide new spaces to debate such strategies. Scholars of urban spatial politics and climate policy have an opportunity and obligation to better engage with one another in support of emerging political debates.

Progressivism in History

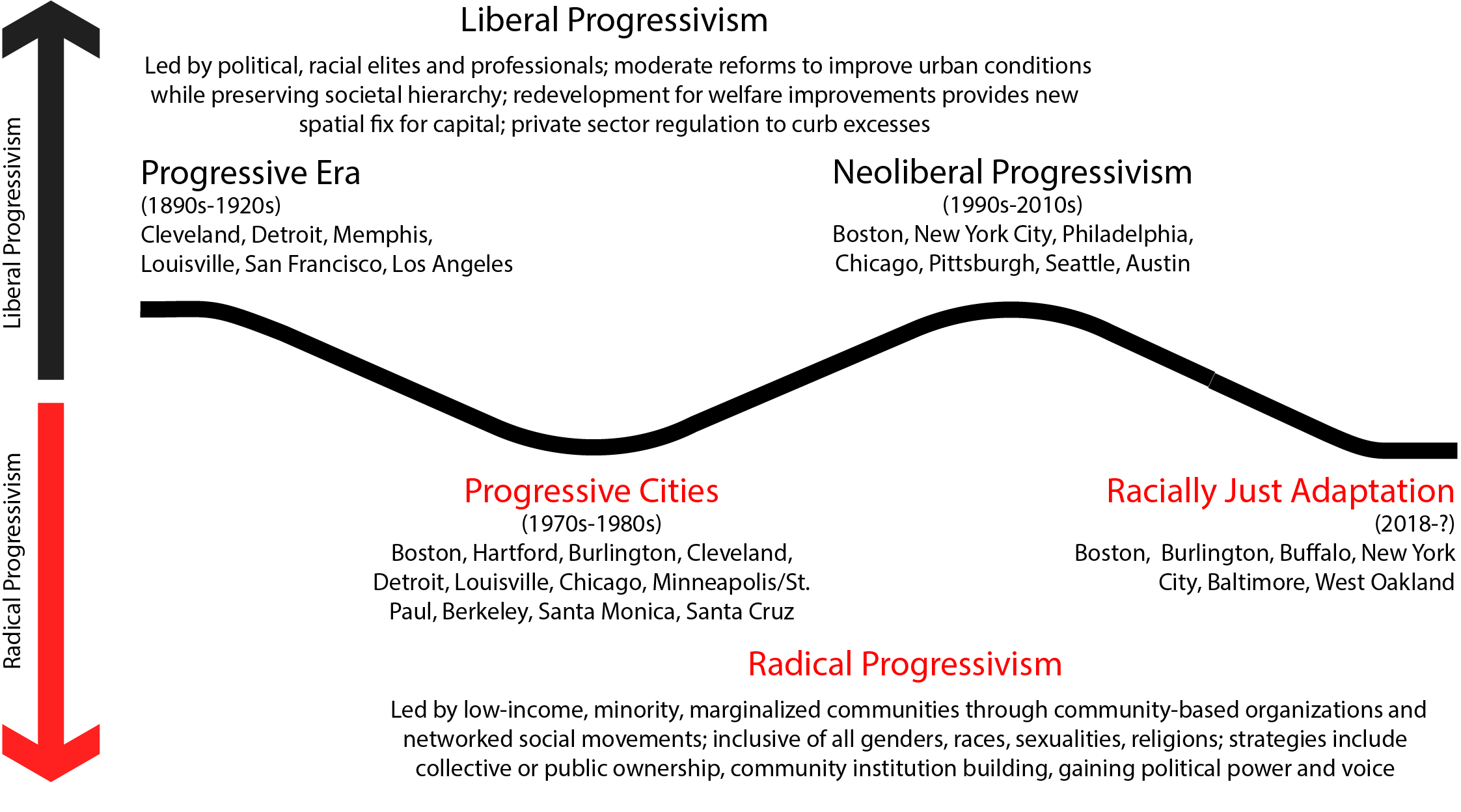

Figure 1. Countercyclical Waves of Liberal and Radical Progressivism

From Theodore Roosevelt’s Progressive Party campaign platform in 1912 to Bernie Sanders’ campaign in 2019, progressivism rests on three key elements: redistribution, democratic process, and administrative reform. Progressives argue that government regulation can stave off the worst excesses of unbridled capitalism by regulating the private sector and redistributing wealth from corporations and elites to the middle or lower-income classes. To achieve redistribution, progressives seek to expand democracy, which can advance procedural justice if communities meaningfully participate in decisions that affect them. Finally, progressives focus on administrative reforms to institutionalize progressive values in government or community institutions.

Over the past century, progressivism has emerged whenever major structural economic and spatial shifts in urban development result in dramatic declines in human well-being. Looking into the future, climate change imposes an unprecedented external shock that threatens existing economic and spatial structures, political and governance systems, and natural ecosystems. These threats and stressors trigger renewed calls for greater social protections, equality in resource sharing, and equal voice in decision making. Abolitionists, Blacks, women, and others have pushed throughout U.S. history for more racial justice reforms within the progressive movement. However, either liberal elites suppress these voices or fragmentation by race and class limits the scope, scale, or geography of radically progressive reforms. As Figure 1 shows, U.S. progressivism has fluctuated between more liberal and more radical tendencies. History suggests that progressivism often fails to live up to its ideals given the challenges of building coalitions across race, class, and geography.

Lessons from History for Current Debates in Climate Adaptation

Today’s efforts to promote racially just resilience closely echo efforts of progressive activists in the 1960s and 1970s to oppose elite redevelopment projects and promote racial justice. These similarities also signal troubling parallels and gaps. Past progressive activists sought political office to implement their actions. Recent reports ask governments to better acknowledge histories of racism and promote social cohesion. Past progressives instituted income and corporate taxes, changed the wage structure, and engaged in direct ownership whether by municipalities or cooperatives to grow the pie. The recent reports ask cities to prioritize marginalized communities for resilience investments and resources without complementary strategies to grow the pie. This pits frontline communities against the middle-class, small businesses, and public agencies in competing for scarce resources. It also ignores the infrastructure, fiscal and land-use policies that commodify land and force cities to maximize land value, and state laws of incorporation that enable municipalities to draw administrative boundaries that protect wealth in enclaves to exclude others.

The 1970s progressive movement was short-lived. Center cities saw themselves as oppositional to suburban municipalities. Rarely did regional coalitions vote to redistribute wealth more equitably. Race and geographically-based organizing divided progressive lobbies from White-dominated labor unions. With no broad base support for national movements, progressive cities could only change so much. Instead, other forces enacted neoliberal fiscal policy at federal and state levels in the 1980s that overwhelmed local progressivism. Community enterprises, housing and business cooperatives, and community land trusts remained pilots and incubators. Today’s equitable adaptation efforts are led by environmental justice organizations that focus on racial injustice. These conversations lack representation from labor unions, suburban communities where poverty is on the rise and where climate gentrification could play out, and rural communities that have also suffered under the political economic system and that could play a key role in climate adaptation and mitigation.

As a matter of movement durability and political opportunism, activists for adaptation justice must move beyond local scales of action to articulate how federal and state governments should address adaptation. To start, I suggest that community organizations, climate think tanks, and urban scholars working at the nexus of equity, justice, and resilience consider:

Coordinating social movements across cities and scales of government to anticipate and resist opportunistic capitalism that is taking advantage of unstable and shifting property markets.

Building bridges between (1) frontline communities in hot property markets, (2) frontline communities in abandoned urban centers, (3) rural White communities, and (4) labor unions.

Working with lawyers, insurance experts, economists, and planners to imagine a different national architecture of land policy. National political debates have yet to discuss land reform, but redistribution must not only account for income but how they are held in land and political jurisdictions.

Creating concrete visions and policy proposals (on par with resiliency design competitions) for how frontline communities in desirable neighborhoods would imagine and control redevelopment that benefits their communities while enabling retreat for others.

Identifying visions of hope that many people can aspire towards, across race and class, beyond narratives of loss and victimization.

Linda Shi is assistant professor at Cornell University’s Department of City and Regional Planning. She researches the spatial politics, planning, governance, and environmental justice of climate adaptation in the United States and Asia. Her current research projects examine the fiscal drivers of municipal vulnerability, rural–urban linkages under climate change, and the impact of property rights regimes on community adaptation. She has a PhD in urban and regional planning from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology.