Housing Vouchers Can Reduce Children’s Exposure to Neighborhood Disadvantage and Be a Tool to Reduce Racial and Ethnic Inequality in Neighborhood Attainment

Andrew Fenelon (Penn State University), Natalie Slopen (Harvard T. H. Chan School of Public Health), and Sandra J. Newman (Johns Hopkins University)

American cities are heavily segregated by race and income, reflecting a legacy of racism and a housing policy heavily tilted toward White suburban homeowners. Recent research suggests that the economic impact of growing up in a poor neighborhood is significant – children can experience reduced rates of economic mobility, which reduces adult earnings and employment. For very poor children, moving to a high-opportunity neighborhood early in life can significantly affect future economic outcomes.

Black and Latino families tend to live in neighborhoods with higher rates of poverty, older and more deteriorated housing, and fewer job opportunities than do White families. Just 20% of poor White children live in low-opportunity neighborhoods, compared to 50% of poor Latino children and 66% of poor Black children. Absent strong and sustained policy investments, low-income families of color have few options for accessing high-opportunity neighborhoods, which can have lifelong implications for economic outcomes.

The federal Housing Choice Voucher program from the US Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) offers the potential opportunity to intervene in this crisis. The voucher program provides a housing subsidy to low-income families, covering the difference between what families can afford to pay and the private market rent cost. Vouchers theoretically offer location flexibility to assisted families, allowing families to use vouchers to move into new neighborhoods that offer greater opportunities or amenities. Empirically, evidence that vouchers provide access to high-opportunity neighborhoods is mixed, and nationwide studies of vouchers’ effectiveness are very limited. Despite the importance of this program as a source of affordable housing for poor families, the number of eligible families greatly outnumbers available vouchers. Most cities develop and maintain lengthy waiting lists for assistance, which average about two years.

We set out to examine to what extent access to housing vouchers affects children’s exposure to neighborhood disadvantage. We used data from the nationally-representative National Health Interview Survey linked with administrative records of HUD rental assistance participation from 1999 to 2014. We merged these data with the US Census and American Community Survey to obtain characteristics of respondents’ neighborhoods. We created an index of neighborhood disadvantage that encompasses neighborhood poverty and income, family structure, education, employment, and welfare receipt. The index has a national average of 0, with higher values indicating more disadvantage and lower values indicating less disadvantage.

Our interest was in the effects of receiving rental assistance on children’s exposure to neighborhood disadvantage. Because the population of families receiving rental assistance is highly select—rental assistance recipients tend to be more economically disadvantaged—a direct comparison of families receiving rental assistance to those not receiving assistance is likely to be biased. As a result, we compared families receiving rental assistance through each program to families who will begin receiving rental assistance within 2 years—the typical length of waiting lists for rental assistance. We call this the “pseudo-waitlist” group, a comparison that enables us to examine causal effects.

We were also interested in how these effects vary by race and ethnicity. As a result, we compared the impact of vouchers on neighborhood disadvantage for non-Hispanic White children, non-Hispanic Black children, and Hispanic/Latino children.

We found that vouchers reduced children’s exposure to neighborhood disadvantage, consistent with expectations that vouchers increase residential flexibility for low-income families (Figure 1). The interesting piece here is that the reduction in neighborhood disadvantage is only found for Black and Latino children, not for White children.

Figure 1: Neighborhood Disadvantage Index by Voucher Status and Child Race/Ethnicity

The notable success of vouchers in reducing exposure to neighborhood disadvantage for Black and Latino children is notable, but should be viewed within the context of overall urban inequality. Notice that while disadvantage declines for Black and Latino current voucher recipients, their level of disadvantage remains well above that of White children, and significantly above US average neighborhood disadvantage (zero, in the case of this index).

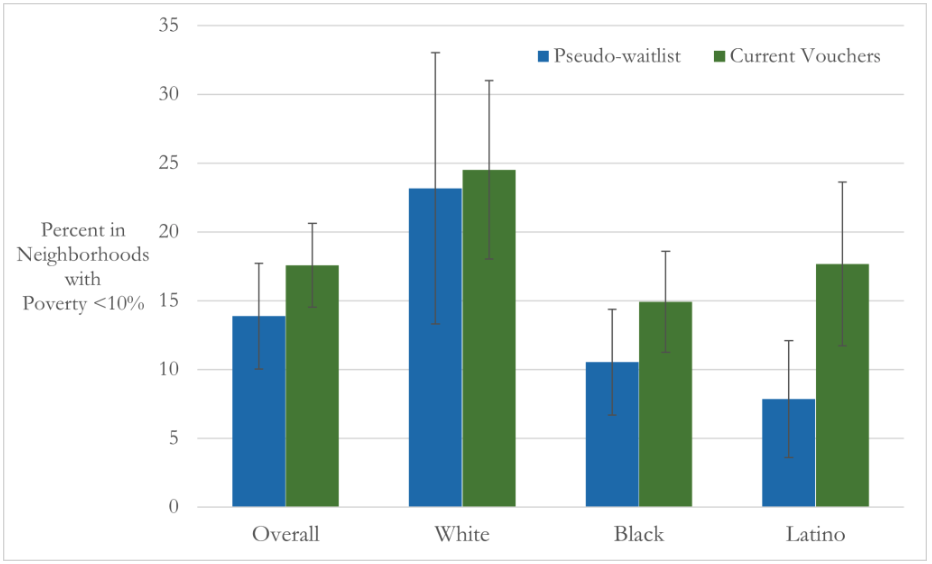

We also examined whether vouchers enable moves to low-poverty neighborhoods (below 10%), since the effective use of vouchers should increase the likelihood that children live in neighborhoods with low poverty rates. Consistent with the disadvantage index results, we showed that vouchers increase the fraction of Black and Latino children living in low-poverty neighborhoods, while we did not see the same effect for White children (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Percent Living in Low-Poverty Neighborhoods by Voucher Status and Child Race/Ethnicity

Federal housing policy has recently emphasized neighborhood mobility as a key policy goal of rental assistance, specifically the housing choice voucher program. Past research has questioned vouchers’ effectiveness in promoting access to high-opportunity neighborhoods, but few studies have specifically attempted to identify a good comparison group.

On a nationwide scale, we showed that vouchers do indeed promote moves that reduce exposure to neighborhood disadvantage. While voucher recipients’ neighborhoods are more disadvantaged than the average US neighborhood, they are a marked improvement over the neighborhoods where recipients previously lived. However, the fact that vouchers have limited success in providing full access to high-opportunity neighborhoods is consistent with past research and suggests that ongoing policy experiments to increase the mobility value of vouchers are well-motivated.

Importantly, we showed that these benefits are found only for children of color, who experienced significantly higher levels of neighborhood disadvantage than White children during the pseudo-waitlist period. As such, vouchers can reduce racial and ethnic inequality in neighborhood attainment. It is essential to recognize that while vouchers reduce the Black-White and Latino-White differences in exposure to high-poverty neighborhoods, White children still live in significantly higher-opportunity neighborhoods, even among children receiving vouchers.

In conclusion, we provide among the most comprehensive picture of the effects of housing vouchers on neighborhood attainment for low-income US children. Our results suggest that while vouchers are a useful and effective tool for improving residential contexts for Black and Hispanic children, there is much work to be done to make good on the promise that each American deserves “a decent home and a suitable living environment.”

Andrew Fenelon is an Assistant Professor of Public Policy and Sociology at Penn State University, University Park. His research focuses on housing policy, population health, and health inequalities. His recent work examines the impact of federal rental assistance programs on health, well-being, and neighborhood attainment across the life course.

Natalie Slopen is an Assistant Professor in the Department of Social and Behavioral Sciences at Harvard T. H. Chan School of Public Health. Her research focuses on the early life origins of health and health disparities across the life course by race, ethnicity, and socioeconomic position. Her work investigates the biological embedding of experiences and conditions in childhood, including housing and neighborhood contexts.

Sandra J. Newman is Professor of Policy Studies at Johns Hopkins University, where she also directs the Center on Housing, Neighborhoods and Communities at the Hopkins Institute for Health and Social Policy, Bloomberg School of Public Health. Newman’s interdisciplinary research focuses on the effects of housing and neighborhoods on children and families, and on the dynamics of neighborhood change.