The Echoes of Echo Park

Anti-homeless Ordinances in Neo-Revanchist Cities

Chris Giamarino (UCLA) and Anastasia Loukaitou-Sideris (UCLA)

Despite continued growth in unsheltered homelessness during the COVID-19 pandemic, policymakers continue to implement and enforce quality-of-life ordinances that criminalize the everyday spatial practices of houseless people. These laws are enforced through police sweeps and target necessary life-sustaining tactics associated with one’s status as unhoused, including camping, loitering, panhandling, and cooking food on public sidewalks and in parks. Their material impacts can be illustrated by expanding anti-homeless strategies like the March 24, 2021 displacement of an autonomous encampment in Echo Park Lake, which resulted in the displacement of 193 individuals and demolition of a community kitchen, garden, and semi-permanent structures, as well as the February 14th, 2023 demolition of a woman’s do-it-yourself semi-permanent structure in Skid Row. Media coverage and street-level anecdotes from activists have sparked heated debates about the expansion of anti-homeless zones, the continued failure of the city to compassionately provide services and permanent housing, and the shrinking rights of unhoused residents to the city. Nevertheless, cities continue to implement more compassionate policies like one-year placements in hotels or tiny homes alongside more aggressive policing and re-enforcement of ordinances in public spaces, as permitted by Martin v Boise which states that quality-of-life ordinances can be enforced if offers of shelter are made. As such, it is important to understand how cities have regulated homelessness through legal and spatial enforcement, and how these spatial banishment strategies have evolved during COVID-19. How scholars and policymakers understand the socio-spatial impacts of quality-of-life ordinances on access to public space and rights to the city for unhoused people amends narratives around the perceived effectiveness of spatial banishment strategies, which helps to reimagine more compassionate policies.

In in a new article in Urban Affairs Review “‘The echoes of Echo Park’: Anti-homeless ordinances in neo-revanchist cities”, we show how cities in the United States criminalize life-sustaining activities associated with the status of being unhoused (i.e, sitting, sleeping, panhandling, and accessing food and water). We find that cities 1) redesign ordinances to criminalize conduct in particular spaces; 2) employ zoning and containment tools like service concentration; 3) conduct routine maintenance under the guise of ‘clean-ups’; and 4) use big data and photography to visualize to pinpoint hotspots for police sweeps. In particular, we focus on a case study of Los Angeles, conducting a content analysis of the evolution of spatial banishment strategies that emerged during COVID-19, which are supplemented by interviews with advocates for the unhoused. Through this case study, we demonstrate that Los Angeles has produced a fragmented landscape of ‘no-go-zones’ for the unhoused (Figures 1 & 2). Here, we argue that Los Angeles is neo-revanchist because the COVID-19 pandemic enabled various spatial banishment strategies that exacerbated socio-spatial exclusion or the unhoused.

Figure 1. Distribution of unsheltered individuals in Los Angeles

Figure 2. Anti-homeless no-go-zones in Los Angeles

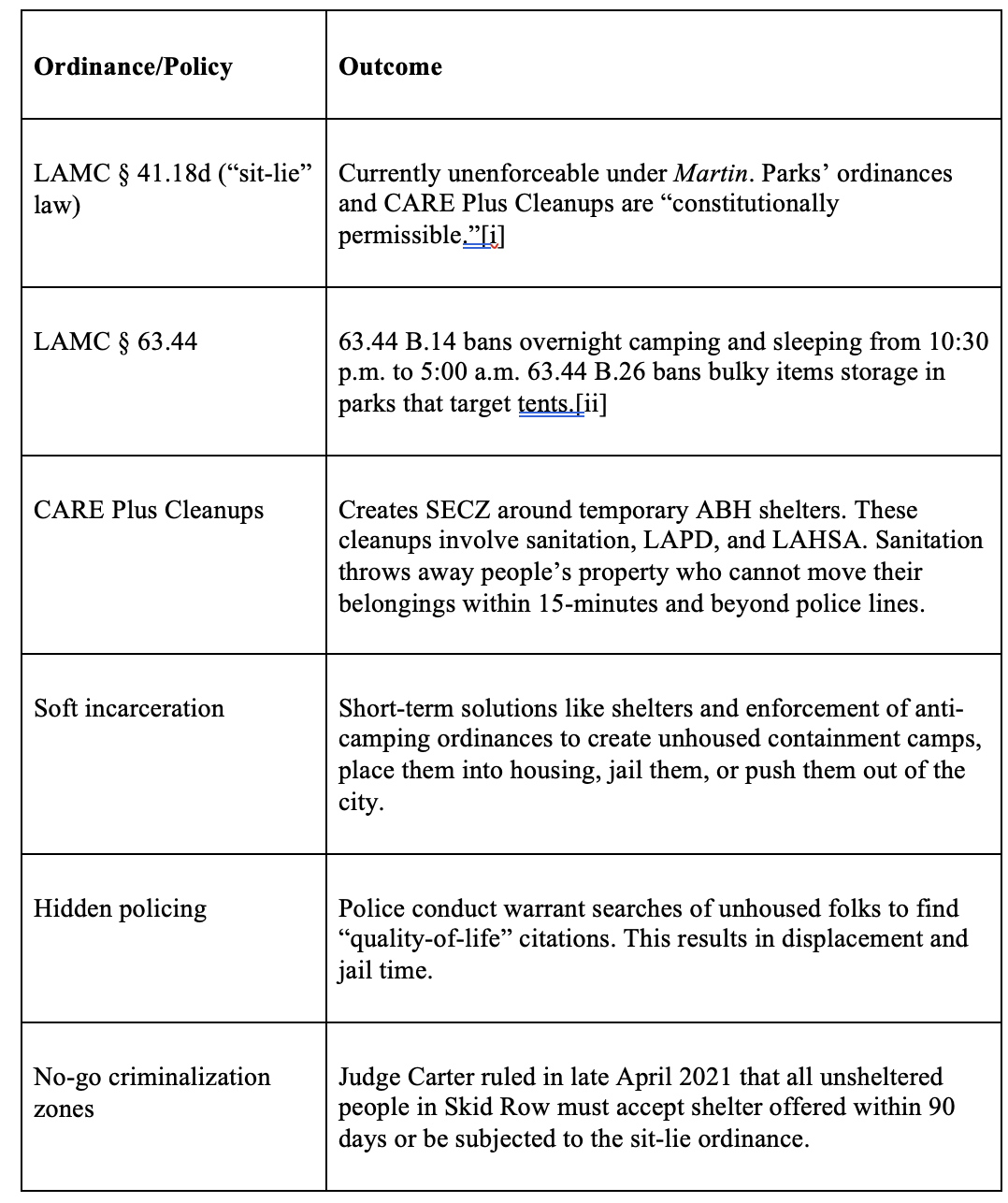

Table 1. City of Los Angeles (In)visible Anti-homeless Policy Landscape

Theoretically, we illustrate how Los Angeles serves as a national example of neo-revanchist responses to homelessness. We move beyond the theoretical counterweights of revanchism (i.e., explicitly punitive responses to police and displace unhoused people from city space) and post-revanchism (i.e., compassionate responses that offer unhoused people services and shelter options when moving them from public spaces). We characterize Los Angeles as neo-revanchist because they continue to enforce quality-of-life ordinances, conduct police sweeps, and produce anti-homeless landscapes, while failing to provide long-term affordable housing (Table 1). Examples include destruction of property, loss of medicine and documentation, arrests and police harassment, and, in one case, death. The spatial result, according to one advocate, is ‘a confusing, haphazard, patchwork system of places where people can and can’t be’.

From our content analysis of media coverage, municipal ordinances, and social media posts about neo-revanchist Los Angeles, and grounded in the voices and experiences of activists who provide mutual aid services in anti-homeless spaces, we offer policy recommendations that can help inform more more compassionate policies for the unhoused. These include 1) including unhoused persons’ voices in decision-making processes; 2) providing public restrooms and showers in public spaces; 3) servicing areas with sanitation services and trash receptacles; 4) replacing armed police with trained service workers during outreach; and 5) making offers of shelter voluntary and less coercive. Moving beyond neo-revanchism, we posit, requires the abolition of spatial banishment strategies in public spaces in exchange for the pursuit of more just policies that unconditionally provide life-sustaining services and permanently affordable housing opportunities.

Read the full UAR article here.

[i] Footnote 8 in Martin (2019, 32) suggests that the ruling is not absolute. It does “not cover individuals who do have access to adequate temporary shelter, whether because they have the means to pay for it or because it is realistically available to them for free, but who choose not to use it.” It also does not rule that “a jurisdiction with insufficient shelter can never criminalize the act of sleeping outside.” Thus, LAMC 63.44, which bans bulky items and overnight camping in public parks, and CARE Plus Cleanups are “constitutionally permissible” under Martin.

[ii] Advocate #5, in conversation with authors, April 2021

Christopher Giamarino is a PhD candidate in Urban Planning at the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA). His dissertation research explores how and why unhoused communities engage in do-it-yourself urban design as a form of resistance and coping.

Anastasia Loukaitou-Sideris is the dean of the UCLA Luskin School of Public Affairs, a former associate dean, a Distinguished Professor of Urban Planning, and a core faculty member of the UCLA Urban Humanities Initiative.