New Books: We Belong Here

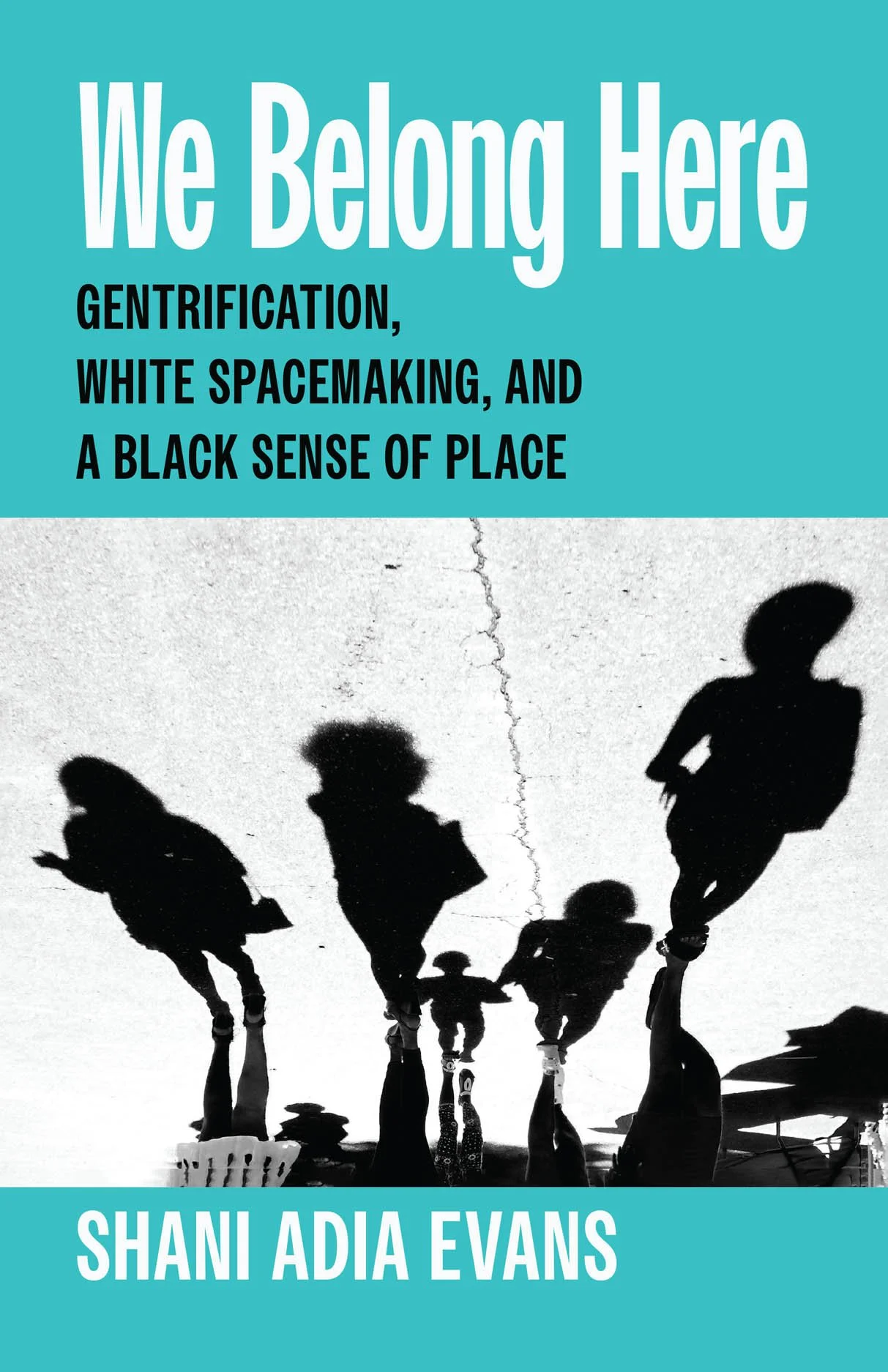

We interview Dr. Shani Evans, author of We Belong Here: Gentrification, White Spacemaking, and a Black Sense of Place, published in 2025 by University of Chicago Press. In We Belong Here, Shani Evans explores the dynamics of gentrification from the inside through a case study of Northeast Portland, OR, a historically black neighborhood. Drawing on a rich inventory of ethnographic fieldwork, this book unsettles some of the economistic determinants around gentrification scholarship and foregrounds the significance of race and racism in neighborhood change.

-

Shani Evans

I was interested in how they experienced the transition of a neighborhood that was a historically black neighborhood into a neighborhood that was majority white, and I found that what they experienced really mapped on well with how Elijah Anderson describes as the white space. And so, I introduced this concept of white spacemaking in the book as the process of making white space and I'm doing that for a couple of reasons. One reason is that when we think about gentrification, when scholars write about gentrification and also in popular discussion and gentrification, we often are talking about class change, new investments in city and neighborhoods. Also, racial change. But the racial change is often understood as kind of secondary to class change, like class change happens and so racial change happens because of the relationship between race and class.

Emily

Hi, this is Emily Holloway, and you’re listening to UAR Remixed, a podcast by the journal Urban Affairs Review. You just heard from Shani Evans, author of We Belong Here: Gentrification, White Spacemaking and a Black Sense of Place from University of Chicago Press.

Shani Evans

I'm Shani Evans and I'm an assistant professor of sociology at Rice University, and I study race and racism, cities and urban change, and social inequality broadly.

Emily

Shani, thanks so much for being here to today to talk about your new book. So, maybe to start, could you share how this project came about? Why Portland?

Shani Evans

Well, the project came from my interest in understanding the experiences of the people who live through displacement and racial change in urban neighborhoods. And I really wasn't seeing work that focused on people who had lived in a place and had lived through that transition, and instead most of the work I was seeing was focusing on gentrifiers focusing on newcomers. I lived in Philadelphia for many years, about 15 years, in West Philadelphia, and I myself, I'm from a suburban community, so I experienced gentrification in this West Philadelphia neighborhood from the perspective of a newcomer, and I had my own experiences as a black person in this neighborhood that raised questions for me about race and neighborhood change, and I also was really influenced by this notion of the white space that was proposed by Elijah Anderson, and so I was thinking about this work and this process of change. When I moved to Portland to work at a college there and it was a huge shift to be in this gentrifying diverse majority black neighborhood to Portland, which is majority white and has a very small black population and I could go a day without seeing another black person, and I found this place Portland particularly interesting to me from the perspective of doing the research, I think there's a lot of reasons why Portland is interesting. You know, for people who study cities. But for me, when I was doing the project, I was thinking about places where the black population is tiny and whether it's a predominantly white space. And I think there are other cities like this in the United States in particular, that I don't really see in the in the research about urban change and about race and everyday experience.

Emily

You mentioned Elijah Anderson and his concept of the white space. Can you unpack this for listeners who might not be familiar with this idea, and how you worked through this framework in your own research?

Shani Evans

So, Anderson wrote an article and then later a book about this notion of the white space, which describes places that are majority white and where when people, black people in particular, mostly people of color more broadly, enter, they are treated with suspicion and have to prove that they can be there, right? So I have to prove through credentials, through making an argument explaining why you're there or by being in your place and not, you know, cleaning or, you know, playing a role that is, that is accepted as a role for this person.

And so I find Anderson is particularly focused on middle class experiences in that and the article in particular and in the book for the most part. And I was interested partly in how people experience these predominantly white spaces and whether people experience them as white spaces as Anderson describes it and I found that framework very useful for making sense of how the people who participate in my study. So I interviewed 45 Black Portland residents, not just people who lived in Portland, with people who had grown up in Portland either were born there or moved there as children.

And so I was interested in how they experienced the transition of a neighborhood that was a historically black neighborhood into a neighborhood that was majority white, and I found that they what they experienced really mapped on well with how Elijah Anderson describes the white space. And so I introduced this concept of white space making in the book as the process of making white space and I'm doing that for a couple of reasons. One reason is that when we think about gentrification, when scholars write about gentrification and also in popular discussion and gentrification, we often are talking about class change, new investments in city and neighborhoods. Also, racial change. But the racial change is often understood as kind of secondary to class change like class change happens and racial change happens because of the relationship between race and class.

And I wanted to have a framework that allows us to think about racial change and focus on racial change in a way that's not dependent on thinking through class change, so that we can think about racial change in a neighborhood and we can think about class change and we can think about how they're connected and how they're reinforcing each other potentially without having to collapse one under the other. And so I think gentrification as a concept is a chaotic concept as we you know, it's not easy to define and I think there are arguments for why we might not want to add new words into the mix, But I think that in this particular case, gentrification has really made it very easy to conflate race and class and to not pay enough attention to how race works. And so white space making is meant to encourage us to think more thoroughly about race and racial change and class and class change, and how these two intersect.

Emily

You also introduce this kind of companion term or analytic, what you call white-watching. How does this fit into this work, or relate to Anderson’s framework?

Shani Evans

I describe this process of white watching in the book to reference the experience of feeling watched, under surveillance in the neighborhood that I study. The experience of Black longtime residents feeling no longer comfortable going into stores and even just walking on the sidewalk because of the treatment and the questioning and the kind of look that seems to ask, why are you here? What are you doing here, which was widely shared across the interviewees. And I think that this is important because again, as I said, the focus on class I think sometimes moves our attention away from actually looking at racial processes. And so there has been a number of works that talk about black or other nonwhite, longtime residents feeling displaced by because of the stores that are in the neighborhood. But often it's because it's explained as an issue of being priced out, they can't afford the stores, so they're not made, they don't feel comfortable in the stores and that, I do see that in my study as well, but I also see these other factors of surveillance and feeling not comfortable and not and treated with suspicion as Anderson right in the neighborhood that had previously been their home.

Emily

Recent work in Black geographies is also really coming through in this book, like work from the geographer Katherine McKittrick. But you also cite bell hooks’ concept of home place, which is really central in the genealogy of Black geographies. How are you engaging with this intellectual framework as a sociologist?

Shani Evans

So, home place is an idea, that bell hooks’ notion of a home place as a refuge from white racism, I focus on interpersonal white racism. It’s a concept that I came to in the process of reading and analyzing the interviews. It's not -- my training did not lead me to home place previously and my work previously and black geographies also was not something that I was even really familiar with until I started this project.

And so it really was me trying to understand what the interviewees were saying and what they're how they were describing their experience and also a recognition of what was missing in urban sociology and how places, black places, are so often represented as places without, as Katherine Mckittrick writes. Places you know, only understood through dispossession, only understood as you know, places where people struggle and not thinking about how people make places and live and redefine geographies in ways that are not wholly defined by white supremacy. And so I found that work, the black geographies kind of theories of black geographies extremely helpful, influential as I was doing the work and also very enlightening for me having come from sociology and really having no exposure to this kind of thinking. But also I think really wanting to find that without knowing that it that it existed.

So in that way it's been really doing this book has been really like a turning point for me in my in my scholarship because it brought me to ways of thinking that I think are so necessary for thinking about black experiences in the city, but that have, and I think are definitely becoming more influential, more present, but has been really absent in past decades and in the work that I was reading as a you know, PhD student in sociology.

Emily

There’s a really memorable and rich anecdote that you share early in on in the book about a focus group with Portland residents that underscores some of these core principles in Black geographies, home place, and so on. Before we segue into talking through some of your methods and interventions, could you talk about this particular experience in the field and how it shaped your approach?

Shani Evans

As part of the field work early in the study, I spent some time with a group of people who were learning about being leaders in the black community, and there was an activity where the group was splitting the two, and one group went to another room and the group that I was in was asked to think about all the problems in the neighborhood and then think about solutions and like I was in that group, the group was very kind of stressed by these questions, they really worked through them. There was a lot of discussion about what were the problems and what were the causes and what were symptoms of deeper causes and ultimately came up with a more stifled list of options that were changed. Solutions that really were outside of their control, largely, and then the other group came into the room, and they had been told to think about all of the strengths. All the things that already existed, and to suggest ways to, you know, build on that and they were much more in a great mood and had great energy, and they came in and they had much more innovative ideas about moving forward. And so, I referenced the kind of theory that the leader of the program was drawing on, which is basically if you do more of what you start with. Basically, we start with the problems you're going to go deeper into problems. So my point in describing that workshop was to point out that I think within Sociology in particular, there's been a kind of a question about whether we should be focusing on positive aspects or negative aspects or the constraining features of life, social life. Like, you know, white supremacy. Or should we be writing about Black joy? Or should we be writing about social lives in ways that emphasize the positive, instead of always having kind of deficit framework, which has characterized most of sociological research on black place? And so in the book I really am trying to not take a deficit framework, but also not focus only on the positive, to try to be kind of in the middle, where I'm looking at what people do, how people do find joy, how people do live, and how people do experience and respond.

But also recognizing that they do so within particular constraints. I also put it in the book because I think it's something to think about like I think it's I think it was a really striking exercise, I think. It's something to think about for organizers, of course. And I also think that for my work, I don't want to only focus on the positive, but at the same time I do want to be very aware of the negative consequences of this deficit framework, which really, even though it's trying to explain inequality, explains how poverty comes to be. For example, has the result again of as McKittrick writes of really describing and redescribing pain and nothing else. And that's not the extent of black life.

Emily

Can you talk about your field work experience a bit more? How did your research questions and even methods and approaches evolve as you talked to more and more people in Portland?

Shani Evans

I think one thing that happened through the process of executing the study is that initially I started the project having moved to Portland. This place is very strange for a black person. What is it like? I mean, there's a lot of wonderful things about Portland, and I think actually, it doesn't come out in the book as how much people really love a lot of the features of Portland and it's beautiful. And there's a lot of, yeah, there's a lot of wonderful things about living in Portland. But my thinking was, what is it like to grow up in this, and that's really what I started on the project. The question I started the project with and then when I started talking to people what they told me is this is not what we grew up with like this is a whole different place than what we experienced 20 years ago,15 years ago.

And so that was so then I shifted and focused on, you know, experiencing that transition. I also kind of thought that I might initially look at people who had grown up there and black people grown up there, and black people who are newcomers and kind of compare. But I ultimately moved away from that, because I thought it was the experiences and the stories were so rich that people who grew up in Portland were sharing, and I really wanted to focus and hone in on those.

Emily

And in terms of interventions, audience – who are you trying to reach with this book? What conversations do you see this book as being a part of?

Shani Evans

When I was writing the book, I was thinking of people who are similarly positioned to the people who I was interviewing and so absolutely I was, you know, thinking about the intervention that the book can make in urban sociology and perhaps black studies, urban studies, but also I think there are ways in which the book shows how people can advocate and have some success in making some changes or resisting some kinds of development, redevelopment projects and how people can organize across class, which I suggest may be more possible in some places than others. I think that's something that needs to be continued to be studied. But based on what I've read in other cities like Chicago, I would expect a lot of class conflict, and I didn't see a lot of class conflict in my project, which doesn't mean it didn't exist.

But what I saw is a lot of organizing across class boundaries to get affordable housing, for example. I think that there are people in, you know, Denver and Seattle and Asheville, NC, and Twin Cities and you know, places where there's a small black population and they've been displaced. So the community has been disrupted. And I wrote the book in part for them and for them to see how people have been successful.

One of the chapters in the book focuses on how the interviewees make sense of how the neighborhood changed, like how they interpret the mechanisms of change. And I think that is important because it led me into directions that I had not already encountered in research on gentrification, although digging I was able to find other work that has similar kind of findings. But you know one article maybe that I was able to find that has a that has a similar findings they're not processes that have kind of risen to our dominant understandings about how gentrification happens, which is why I think again, white spacemaking helps us recognize and focus on processes that we may miss if we're focusing on class change and these included policing, and this policy that allows people to be excluded from the neighborhood, it includes liquor licensing and whether people were able to sell liquor or alcohol in their stores, or whether in the different kinds of the different kinds of constraints that are put on clubs that play hip hop, for example, that make it hard for black people to congregate in public space. So, there are a number of processes that came out of the that I flag in the book that I think only were identified because I was asking questions about race and racism, and only because I was interested in how the people who experienced this transition made sense of it. And so again, this is what I have not seen enough of, and I think that if people continue to focus on trying to understand that perspective, then we'll expand our understanding of how cities change.

Emily

I also think your book is making pretty significant interventions into questions around racial capitalism, like you mentioned a few minutes ago. These debates around the primacy of race versus class in urban change, structural inequality, and importantly for this study, gentrification. You had mentioned early on, gentrification is this rather chaotic concept in urban studies, it can signify so many different dynamics and there’s not a clear consensus among researchers on why it happens but also how it relates to more generalized trends or patterns under racial capitalism. How are you working through these debates?

Shani Evans

The book is called We Belong Here: Gentrification, White space-making, and a Black Sense of Place. And that's intentional in the sense that I'm not trying to argue that we shouldn't be talking about gentrification or that white space-making is more important than gentrification or anything that's like disparaging the notion that we should be setting justification. And I try to be clear that I don't think that white space-making or racial change is more important than class change or more significant than, you know, the ways that people profit off property in ways that harm poor people and working-class people. But what I'm trying to point out is that because gentrification has been used to mean all of the things it facilitates a process of conflating race and class, it makes it easier to talk about class and to kind of assume or suggest that the reader should know that they're also talking about race So that's the assertion that I'm making by insert by inserting white space-making, is that having a word that means all kinds of change is going to result in studies that don't involve enough examination of the different kinds of changes and how they relate to each other. Shouldn't say it's going to, but it has and so it's messy, but I think it's necessary in order for us to have a better understanding of how these different processes affect the people who live in urban neighborhoods.

Emily

My thanks to Shani Evans, author of We Belong Here, from University of Chicago Press. You can find a link to the book in our show notes.

You’ve been listening to UAR Remixed, a podcast by Urban Affairs Review. Special thanks to Drexel University and the editors at UAR. Music is by Blue Dot Sessions. This show was mixed and produced by Aidan McLaughlin and written and produced by me, Emily Holloway. You can find us on Bluesky at @urbanaffairsreview.bsky.social for updates on the journal and the show. Please rate, review, and subscribe on Apple, Spotify, or wherever you get your podcasts.