When Cues Collide

Partisan Signals and the Dynamics of Ethnic Voting in Nonpartisan Local Elections

E. Grant Baldwin (UCLA)

In many city elections across the United States, voters face a similar challenge: they are asked to choose among candidates they know very little about. Ballots often list only names, not party labels, and local races receive little media attention. In these low-information settings, voters look for clues that can serve as “shortcuts,” or anything that will help them quickly decide which candidate to vote for.

One pattern appears again and again: when a local candidate shares voters’ racial or ethnic background, those voters are more likely to support them. Black voters tend to favor Black candidates for mayor and city council; Latino voters tend to favor Latino candidates. Political scientists call this “ethnic voting,” and it has been observed across multiple minority groups in American cities for more than a century.

Research Question

My research asks: is ethnic voting mainly a response to the lack of information in local elections, or does it reflect concerns that are unique to city politics?

One existing explanation emphasizes information. Because most city elections are officially nonpartisan, voters often lack clear signals about where candidates stand on policy. Rather than researching every candidate in a contest in detail, voters instead may rely on the limited information available on the ballot to guide their choices. Names and brief biographical details can signal a candidate’s background, and voters may use these cues to infer how candidates are likely to govern. In this context, supporting a co-ethnic candidate can be a practical shortcut under an assumption that someone with a similar background is more likely to share one’s priorities.

A second explanation focuses on the nature of local government itself. City politics is often less about ideology and more about who receives public services, attention, and representation. From this perspective, voters may see local elections as contests between groups competing for influence over scarce resources. Supporting a co-ethnic candidate, then, may not be just about guessing a candidate’s views from limited information, but about ensuring one’s community has a voice inside city hall.

While these two explanations are not mutually exclusive, there are certain outcomes we would expect to observe if one is operating more than the other. For instance, if ethnic voting is mostly a product of a low-information environment, we might see it decline if more information about the candidates is available—i.e., a Latino voter sympathetic to the Democratic party may vote for a non-Latino candidate they know is a Democrat over a Latino candidate without a party label. Alternatively, if ethnic voting is more about group conflict, we should see it occurring more frequently in places where conflict between groups is more likely and might persist even if more candidate information is available.

The Study

To answer my research question, I analyze the results of more than 100 mayoral elections held in California cities between 2010 and 2021. Each of these elections includes at least one Latino candidate running against at least one non-Latino candidate.

Although all mayoral elections in California are officially nonpartisan, candidates sometimes make their party affiliations clear to voters outside the ballot. For example, in Sacramento’s 2016 mayoral race, Darrell Steinburg ran without a party label, but his service as a Democrat in the California State Senate made his affiliation widely known. Across the elections I study, I classify candidates as either true nonpartisans—those whose party ties where not publicly visible—or revealed partisans—whose affiliations were evident through media coverage, campaign materials, or prior campaigns for or service in partisan offices. About one-fifth of all candidates fell into this second category, and just over half of the elections studied were fully nonpartisan, meaning no candidate publicly disclosed a party affiliation.

To test the role information plays in shaping ethnic voting, I compare how Latino candidates perform in heavily Latino election precincts across elections where party information was absent versus elections where it was visible.

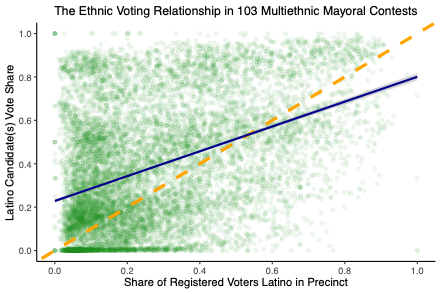

Figure 1. The Ethnic Voting Relationship in 103 Multiethnic Mayoral Contests

Finding 1: Latino Candidates Do Better in Latino Precincts in Fully Nonpartisan Elections

In elections where no candidate publicly reveals a party affiliation, Latino candidates receive more support as the share of Latino voters in a precinct increases. In other words, heavily Latino precincts consistently give more votes to Latino candidates when party information is absent. This patten holds even after accounting for differences between cities that might otherwise make voters more sympathetic to Latino candidates.

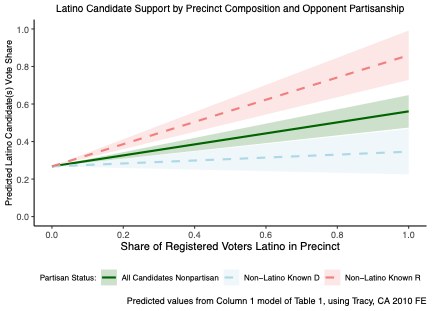

Figure 2. Latino Candidate Support by Precinct Composition and Opponent Partisanship

Finding 2: Party Information Changes How Ethnicity Shapes Voting

The pattern of ethnic voting shifts once candidates’ party affiliations become visible. The direction of that shift depends on who reveals their party and which party it is.

When a Latino candidate is a known Democrat, they receive roughly the same level of support in heavily Latino precincts as they would if they did not reveal their partisanship. By contrast, Latino candidates who are known Republicans face severe penalties in heavily Latino precincts.

The party affiliation of non-Latino candidates also matters. Heavily Latino precincts tend to give less support to Latino candidates when a non-Latino opponent is a known Democrat. But, when the non-Latino opponent is a known Republican, those same precincts give even more support to Latino candidates than they do in fully nonpartisan races.

These patterns hold even after accounting for differences in candidate name recognition and experience, and they are strongest in places where Latino Democrats far outnumber Latino Republicans.

Finding 3: When Ethnicity Might Matter More Than Party

In cities with higher levels of non-Latino–Latino residential segregation and wide economic gaps between Latino and non-Latino residents, Latino known Republicans are penalized less for their party affiliation, suggesting that sharper group boundaries can make shared ethnicity more politically important than party alone.

Takeaways and Political Implications

In city elections, voters appear to vote based on what they know. Ethnicity matters when party cues are absent, but visible partisanship can override it. These findings might also inform candidate strategy: non-Latino candidates may attract more Latino votes by revealing Democratic partisanship, while Latino Republicans may do better by keeping their party affiliation hidden.

Eric Grant Baldwin is a PhD Candidate in Political Science at the University of California, Los Angeles. His research broadly covers topics in representation, voting behavior, and public opinion, with a particular focus on local, urban, and state politics in the United States.