Political Architecture: Contextual Development and Opposition to Housing

Adrian Pietrzak (Princeton University) and Tali Mendelberg (Princeton University)

Over the past few years, the architecture of new apartment buildings has received significant attention. In particular, a style of new building sometimes called “fast-casual” or “gentrification architecture.” Many readers may recognize these buildings: blocky, generally black-and-white (although some come with neon pops of color), and unornamented. They’ve inspired countless debates, with critics calling them ugly and bland, or more creatively “Lego structures” and “oversized tin cans.”

At the same time, U.S. cities have continued to pass laws which regulate the architecture of new development and aim to maintain the existing look-and-feel of neighborhoods. Historic districts, like those recently created in Philadelphia, require new construction to go through discretionary review. Contextual zoning regulations, which transformed New York City, don’t allow new buildings to differ much in size or bulk than their surroundings. Design review regulations, like Seattle’s, involve city staff (and sometimes public) review of building appearance and how it relates to existing buildings in the neighborhood.

The Research Question

To what extent are these observations reflections of popular opinion about new development? Specifically, we ask: does building architecture (style and height) impact support for new development? How about the “fit” of new buildings relative to existing neighborhoods?

The Study

To answer these questions, we ran a survey experiment with about 1,500 metropolitan area Americans. We asked them if they would support or oppose the construction of eight buildings that differed in height (2, 4, 5, or 8 stories) and style (modern or a traditional brick). To make these buildings realistic and to avoid imposing a label on them, we showed image renderings, like many proposed developments. We specified other factors like affordability and parking, and kept them identical across conditions, so they cannot explain the effects.

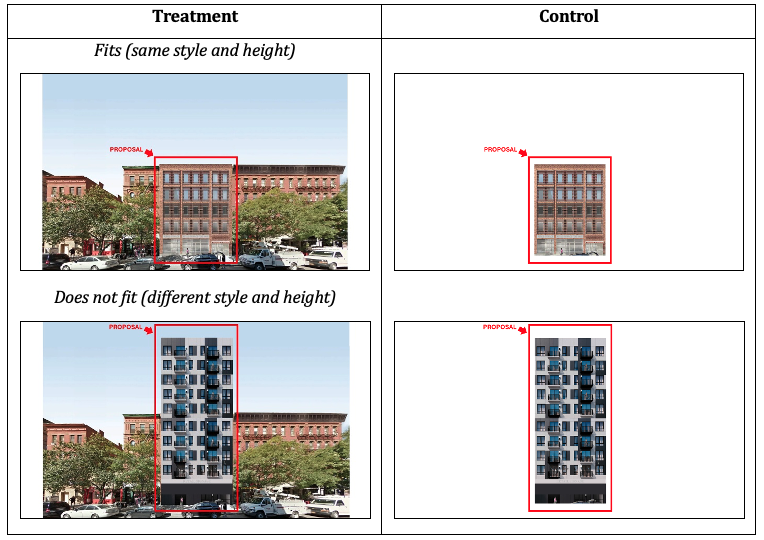

Half of our participants were in the control group, meaning they were asked about the eight buildings without seeing the neighborhood context. The other half of our participants, the treatment group, saw these same eight buildings with neighborhood context (we chose two traditional style historic neighborhoods). Figure 1 shows how a building was shown in treatment and control.

Figure 1. Examples of Treatment and Control Renderings

Finding 1: People Dislike Tall Buildings, but Style Doesn’t Matter

First, we look at the control group. By comparing support for the eight buildings without neighborhood context, we can estimate using statistical techniques how important height and style are on their own.

Height, unsurprisingly, was disliked. Relative to a 2-story building, 10-story buildings got about 8 percentage points less support. Style, on the other hand, had no impact. In fact, when we asked our respondents to rate how “attractive” they found the buildings, the modern buildings were rated as more attractive, though this didn’t affect support for the building.

This finding shows that building height is more important than style when people decide how supportive they are of new buildings.

Finding 2: People Dislike Buildings Which ‘Don’t Fit’ Neighborhoods

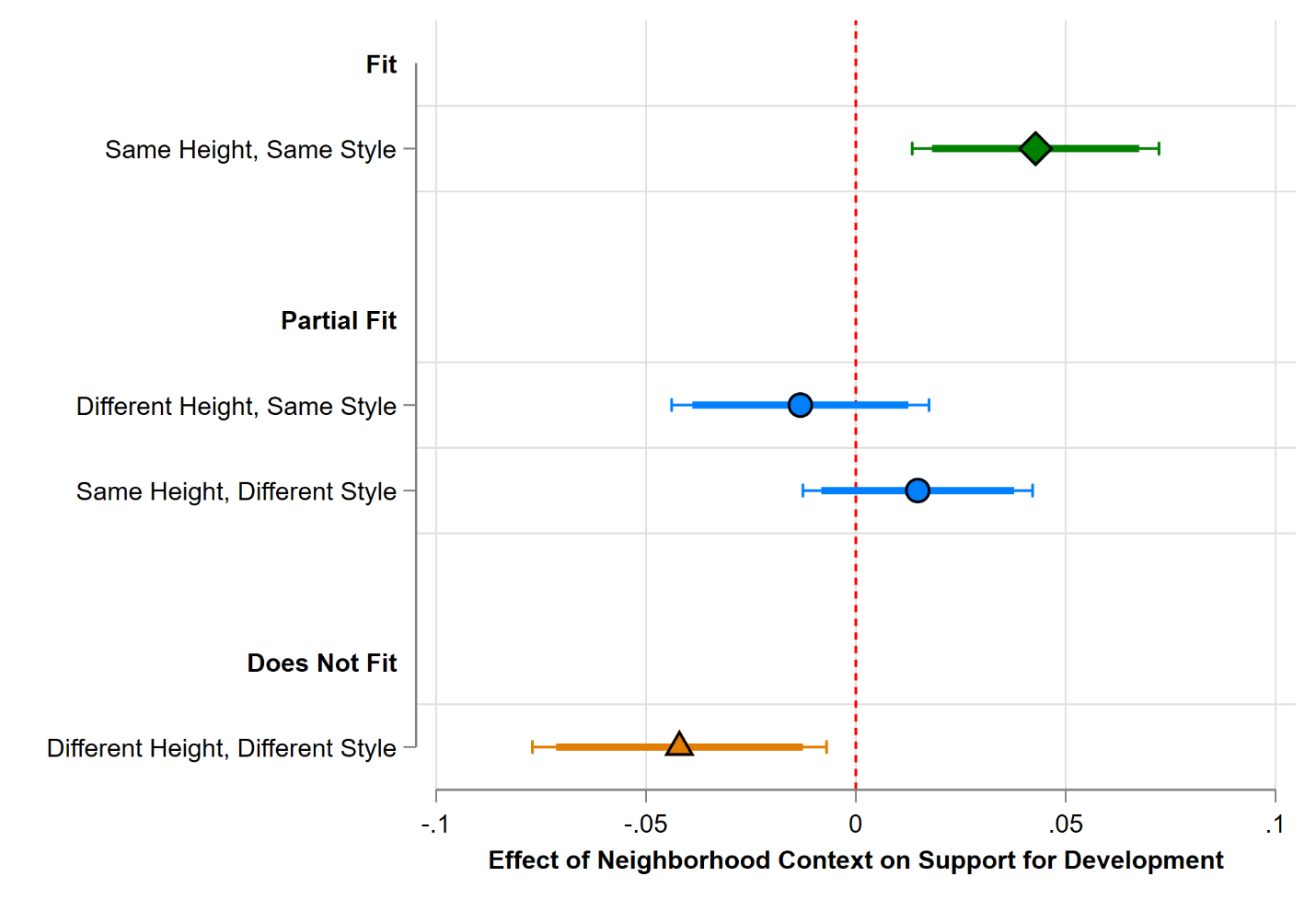

Second, we estimate how support changes for a building if it “fits” the neighborhood context. A building “fits” if it matches the style and height of surrounding buildings, “partially fits” if it matches just one, and “doesn’t fit” if it matches neither style nor height. We can estimate how support changes for buildings which fit or do not fit by comparing the same buildings in the treatment group (with neighborhood context) to the control group (without neighborhood context). Figure 2 shows these results.

We find that buildings which fit in are supported by about 4 percentage points more than the same buildings where context wasn’t shown (the green diamond). Similarly, buildings which don’t fit in either height or style were supported by 4 percentage points less (orange triangle).

Figure 2. Treatment Effect of Neighborhood Context on Support for Building

We also find that partial fit didn’t matter (the blue circles). While modern buildings were disliked at higher rates in our treatment group, this effect is small, only about 2-percentage points. Most of the effect was driven by building height.

Finding 3: Tradeoffs Matter, but Many Are Willing to Pay the Price

To reduce housing costs and address the affordability crisis, a significant amount of denser multifamily housing is required. However, traditional styles are more expensive to build (costs). Meanwhile, taller buildings can be cheaper per unit and often provide additional benefits to the community such as Community Benefit Agreements (benefits). We informed our participants about these costs and benefits.

Then, we had them choose between a building which fit and one which didn’t fit. When we imposed a cost on the building which fit, 12 percent fewer people chose that building. When we gave the building which fit a benefit, support increased 18 percent more people chose that building. However, the majority (about 60%) still chose the shorter, traditional building which fit in the neighborhood despite these tradeoffs.

Takeaways and Policy Implications

We find that preferences for buildings “fitting in” to neighborhoods are meaningful. Many people hold these views (including renters, homeowners, urbanites, and suburbanites). Moreover, opposition increases when buildings “stick out” and are taller and a different style than their surroundings. We also find that buildings which don’t fit motivate costly behavior (saying you’d attend a meeting), whereas buildings which fit do not. This may explain common not-in-my-backyard (NIMBY) opposition to buildings which don’t fit.

We find that most of this effect is driven by height. The effect of style is small. Mobilizing support for densification is not as simple as changing the style of proposed buildings. For policymakers, this suggests that stylistic policy interventions, like design review, are likely ineffective in generating substantial increases in support for dense or affordable housing.

Rather, our results highlight the importance of carefully designed land-use regulations. We find that existing regulations and the buildings they create and change future support for new development. Therefore, regulations which create uniform heights can preclude future densification. Regulations which encourage a diversity of heights, bulks, and building designs can help improve support for housing development in the future.

Adrian Pietrzak is a Ph.D. student in Politics and Social Policy at Princeton University. He received his B.A. in Politics and Economics from New York University in 2019. He studies American urban politics, with a focus on the politics of land-use. He is also an Associate Policy Fellow at Reinvent Albany.

Tali Mendelberg is the John Work Garrett Professor of Politics at Princeton University, co-director of the Center for the Study of Democratic Politics, and director of the Program on Inequality at the Mamdouha S. Bobst Center for Peace and Justice. She is the author of The Race Card: Campaign Strategy, Implicit Messages, and the Norm of Equality and The Silent Sex: Gender, Deliberation and Institutions (with Chris Karpowitz).